by Jill Amadio

Teach a writing class? I have enough trouble getting myself to work on my next mystery, of which I only have one-third finished. However, I am working full-speed on my new career as a writing coach.

Westport, CT, has more than its share of elderly, I was told at the town’s country-club-style senior center where I use their gym. The executive director figured many of the members would love to write their life story if only they knew how.

Interesting, I thought, because I have been looking for a paying job. I’ve written four biographies under my own name and a few as co-author. My greatest contribution to assisting another person’s attempt to get their autobiography on the page has been as a ghostwriter. I’ve written 15 for clients. This is the kind of book you can write with no repercussions tied to your own fragile persona. No one can take potshots at you for you putting on the published page swipes or dislikes for certain relatives, remembered experiences that showed others as fools, or perhaps an opportunity to lay bare your absolute hatred of your cousin’s prize poodle. I do, however, urge a client’s caution, and I try to appeal to their good nature if they have one.

So, did I want to take up the challenge of teaching some old fogies like myself how to write their memoirs? The idea appealed to me. I had never taught anyone anything in my whole life. Well, maybe a few table manners to my kids. So, yes, I accepted the challenge to help anyone over 65 jot down their life story in presentable and publishable form.

So, did I want to take up the challenge of teaching some old fogies like myself how to write their memoirs? The idea appealed to me. I had never taught anyone anything in my whole life. Well, maybe a few table manners to my kids. So, yes, I accepted the challenge to help anyone over 65 jot down their life story in presentable and publishable form.

Creating a curriculum was my first worry. What would I teach? The elements of style came immediately to mind. I’d want to know how to structure a book, create my personal style, and how to write down my thoughts and feelings. I’d want to know how to describe places and people, events and experiences that had made up my world since birth and were still occupying my psyche both physically and mentally.

For the first class, I asked my students to create a Timeline, a list of each year of their life with a significant note, and a few words to mark why it was memorable.

I decided that handouts were important because I had always loved receiving them at writers’ conferences, so I found Rudy Vallee’s timeline I’d created back in 1989, as well as a champion cowboy’s timeline that chronicled his trek across America from coast to coast on horseback. One handout was a list of 106 descriptive verbs I’ve used for years.

In addition to the Timeline, I also mapped out writing techniques and elements for the following classes. In addition to Structure, Style, and Context, I added how to write Characters, Flashbacks, Settings, Cliffhangers, Editing, Beginnings and Endings, Publishing, and Marketing. I became so enamored of my advice I began to inspect my own WIP and make changes. I dredged up a few tips and notes I’d taken at various conferences and thus was able to flesh out my curriculum.

An observation about the students. They were extremely keen to learn how to write their memoirs. It was clear some of them had been thinking about writing such a tome for a few years but had no idea how to do it. By the homework I gave them, i.e. the Timeline, they returned to class time and time again more enthusiastic than ever. I told them to always interrupt me any time with questions, hoping that my fear they’d forget them before the end of class was not apparent.

Among these senior students, limited to 12, were a school bus driver, a poet, an attorney, an ad saleswoman, a lady from Germany who escaped the Nazis, a couple of teachers, a financier, and an accountant. One gentleman dropped out after lesson #2 because he said now that he was about to describe his life, he found it too painful to do so. Another gentleman said he doubted he would continue because as a reporter, he was trained to write lean, and that was the antithesis of writing a book. I told him I’d initially experienced the same hesitation when I was first approached about ghostwriting. My editor at the magazine I wrote for said that a CEO had called asking for a referral to a writer for his business book. Before calling him back with a recommendation, she asked me if I’d be interested.

Among these senior students, limited to 12, were a school bus driver, a poet, an attorney, an ad saleswoman, a lady from Germany who escaped the Nazis, a couple of teachers, a financier, and an accountant. One gentleman dropped out after lesson #2 because he said now that he was about to describe his life, he found it too painful to do so. Another gentleman said he doubted he would continue because as a reporter, he was trained to write lean, and that was the antithesis of writing a book. I told him I’d initially experienced the same hesitation when I was first approached about ghostwriting. My editor at the magazine I wrote for said that a CEO had called asking for a referral to a writer for his business book. Before calling him back with a recommendation, she asked me if I’d be interested.

“A book? A whole book? No way!” I said. “I enjoy writing the 3,000-word articles for the magazine, but 70,000 words? Forget it.”

“Think of it this way,” the editor said. “Approach each chapter as an article. And the pay is really good.”

“Oh. Okay, I’ll do it.”

After that first book, I received many referrals and became a ghostwriter. A few people contacted me through my website, www.ghostwritingpro.com. One client, a banker, asked me to ghostwrite her novel about financial fraud.

“Hmm,” I said. “Sounds a bit boring. How about we add a murder to spice it up?”

“Yes! How many murders can we have?”

The publishing of that book inspired me to create my own Tosca Trevant mystery series while I continued to ghostwrite as my main source of income.

Back to my seniors’ class. The atmosphere was informal, friendly, and focused. I showed them several of my memoirs and said that although we only had eight hours in total with which to cover the subject, it at least would get them started thinking and planning.

By lesson #4, we all felt comfortable with each other reading aloud the homework. One lady was writing her memoir only for her grandchildren and refused to share it with us. But everyone else was eager for everyone’s critique. The lawyer fella incorporated funny poems into his memoir, and someone else brought us to chuckles with her descriptions of working in a donut shop as a teenager. The German lady brought us to tears with her childhood memories of fleeing the Nazis

By lesson #4, we all felt comfortable with each other reading aloud the homework. One lady was writing her memoir only for her grandchildren and refused to share it with us. But everyone else was eager for everyone’s critique. The lawyer fella incorporated funny poems into his memoir, and someone else brought us to chuckles with her descriptions of working in a donut shop as a teenager. The German lady brought us to tears with her childhood memories of fleeing the Nazis

That first 8-hour course was popular enough to be repeated, and later in the spring, I shall be teaching How to Write a Short Story or Essay. Luckily, when I lived in Laguna Woods, CA several of my stories were published in the community’s anthologies over the years, although I can’t remember ever writing an essay. Tips for my seniors, anyone?

.

Jill’s article was posted by Jackie Houchin

I recently had a book published by Austin Macauley about my work as a pet detective. It is a work of ‘faction,’ as I like to call it. Some stories are true, some are fiction, and some are combined (real and made up).

I recently had a book published by Austin Macauley about my work as a pet detective. It is a work of ‘faction,’ as I like to call it. Some stories are true, some are fiction, and some are combined (real and made up). I’ve always enjoyed spring, a time of renewal, and probably more so this year after the winter we’ve been through. Thoughts turn from shoveling snow to shoveling dirt in the garden, from watching the overflowing rivers subside to marveling at the regeneration of fauna and flora.

I’ve always enjoyed spring, a time of renewal, and probably more so this year after the winter we’ve been through. Thoughts turn from shoveling snow to shoveling dirt in the garden, from watching the overflowing rivers subside to marveling at the regeneration of fauna and flora.

I can still recall presenting Chapters 1 – 5 of what is now my first novel, A Petal in the Wind. I’d compressed what eventually became my entire novel into fifty pages. I also recall the group’s unanimous opinion: to put it kindly, not good, but they explained WHY. No character development, hardly any scene setting or sensory details, and worst of all, an unrealistic reaction by my protagonist, thereby committing the worst crime in fiction by presenting a totally unbelievable situation. Their comments were tough to hear, but I listened and took them to heart. The next time I presented pages for critique, I received a very different response.

I can still recall presenting Chapters 1 – 5 of what is now my first novel, A Petal in the Wind. I’d compressed what eventually became my entire novel into fifty pages. I also recall the group’s unanimous opinion: to put it kindly, not good, but they explained WHY. No character development, hardly any scene setting or sensory details, and worst of all, an unrealistic reaction by my protagonist, thereby committing the worst crime in fiction by presenting a totally unbelievable situation. Their comments were tough to hear, but I listened and took them to heart. The next time I presented pages for critique, I received a very different response.

Three days later Allan and I bid ahoj to Prague and boarded a train bound for Poland. After an overnight stop in Katowice, the largest city in the region known as Upper Silesia, we took a cab to the nearby city of Bytom, the hometown of my father and his entire family. Back then Upper Silesia was part of Germany, the city known as Beuthen. As I walked along the streets, I tried to picture what his life must have been like. I gazed at the people who passed, wondering if I’d see any signs of familiarity in their faces.

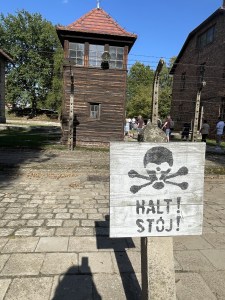

Three days later Allan and I bid ahoj to Prague and boarded a train bound for Poland. After an overnight stop in Katowice, the largest city in the region known as Upper Silesia, we took a cab to the nearby city of Bytom, the hometown of my father and his entire family. Back then Upper Silesia was part of Germany, the city known as Beuthen. As I walked along the streets, I tried to picture what his life must have been like. I gazed at the people who passed, wondering if I’d see any signs of familiarity in their faces. Entering into the first camp, with its ARBEIT MACHT FREI (“Work sets you free”) sign over the entrance gate, I wondered how I would react, or feel. I’m still not sure, to be honest, other than the eerie familiarity of what I heard and saw – from decades of studying photographs accompanied by written accounts, of documentaries and movies filmed on location, and stories I’d heard from survivors, including my father. For many, the trip was a history lesson. For me, it was akin to visiting the cemetery; I lost an estimated ninety members of my family there.

Entering into the first camp, with its ARBEIT MACHT FREI (“Work sets you free”) sign over the entrance gate, I wondered how I would react, or feel. I’m still not sure, to be honest, other than the eerie familiarity of what I heard and saw – from decades of studying photographs accompanied by written accounts, of documentaries and movies filmed on location, and stories I’d heard from survivors, including my father. For many, the trip was a history lesson. For me, it was akin to visiting the cemetery; I lost an estimated ninety members of my family there. After a brief break, the tour continued to nearby Birkenau. Unlike Auschwitz, which to me felt small and claustrophobic, Birkenau is huge. You’ve seen it in many movies: a long low building with railroad tracks leading to a central tower, open at the bottom to allow trains to enter with their human cargo, like a gaping maw ready to devour all who arrive. Alongside and beyond the entrance, what seems like miles and miles of barbed wire fencing surrounds a huge open area interspersed with low barracks and guard towers. In the distance I could see different tour groups traversing the grounds, and for one brief moment I pictured them in the striped uniforms and hats of prisoners.

After a brief break, the tour continued to nearby Birkenau. Unlike Auschwitz, which to me felt small and claustrophobic, Birkenau is huge. You’ve seen it in many movies: a long low building with railroad tracks leading to a central tower, open at the bottom to allow trains to enter with their human cargo, like a gaping maw ready to devour all who arrive. Alongside and beyond the entrance, what seems like miles and miles of barbed wire fencing surrounds a huge open area interspersed with low barracks and guard towers. In the distance I could see different tour groups traversing the grounds, and for one brief moment I pictured them in the striped uniforms and hats of prisoners.  Prior to abandoning the camp in January 1945, days ahead of the advancing Russian forces, the Nazis burned the meticulous records they’d kept of all who were brought to the camps and blew up the gas chambers. Only piles of rubble remain. Many, many piles. They left behind the prisoners too weak to continue; the rest (including my father) went on a forced march from one concentration camp to the next, always trying to stay ahead of the Russians, whom they rightfully feared more than the other Allies. It took several more months until my father was liberated, but at least the Americans freed him. Had he stayed behind in Auschwitz, he would have lived the rest of his life under the thumb of the Soviets. After what I saw in Bytom, I’m grateful he had the strength to wait.

Prior to abandoning the camp in January 1945, days ahead of the advancing Russian forces, the Nazis burned the meticulous records they’d kept of all who were brought to the camps and blew up the gas chambers. Only piles of rubble remain. Many, many piles. They left behind the prisoners too weak to continue; the rest (including my father) went on a forced march from one concentration camp to the next, always trying to stay ahead of the Russians, whom they rightfully feared more than the other Allies. It took several more months until my father was liberated, but at least the Americans freed him. Had he stayed behind in Auschwitz, he would have lived the rest of his life under the thumb of the Soviets. After what I saw in Bytom, I’m grateful he had the strength to wait. Before we go on to some inspiring quotes from a dozen great mystery writers, here’s a little housekeeping to help you get the most from our blog.

Before we go on to some inspiring quotes from a dozen great mystery writers, here’s a little housekeeping to help you get the most from our blog.

You must be logged in to post a comment.