By Miko Johnston

My late father co-founded a non-profit organization dedicated to Scandinavian philately. In addition to translating and publishing educational books on the subject, the group held monthly meetings as well as annual exhibitions where members could present their best work. Dad served as their president for many years; his name and phone number appeared on all contact sources.

He wasn’t home the day a young man called for more information about the organization. I offered to answer as much as I could. His first question: “Can you join if you’re under eighteen?” Yes, I told him, there is no age limit. “Can I bring another guy to the meetings?” Sure, I said, but something told me he had something, um, different in mind. I then said, “You do realize that philately is stamp collecting.”

“Oh.” He promptly hung up.

We spend a great deal of time writing about words on this blog. If you hunt through our archives, you’ll find many posts on the topic, which should come as no surprise. Words are the most important tool in a writer’s toolbox. We think about them, which one to use in any situation, whether a particular word or one of its cousins (aka synonyms) would be more precise, more distinctive. Can we convert that verb/adverb pairing into one verb? How many descriptives can we edit out without losing the image, the rhythm, or the voice of a character?

Words convey and put into context images, thoughts and ideas, especially when they’re carefully selected. We have non-verbal ways of communicating as well, but unless there’s some established pattern to it, such as sign language or Morse code, their subtlety makes them less effective for interpretation – is she slouching because she’s humiliated, or her back hurts?

Whether spoken or written, signed or signaled, we rely on words as the basis of communication. Misinterpretations may cause embarrassment, as my earlier story shows, but in the right hands they surprise in an entertaining way. Writers can inform the reader without the character’s knowledge, a technique I relied upon in my first novel, when my protagonist was a child. Or they can make the reader wait – ideally with keen anticipation – for information the character already knows.

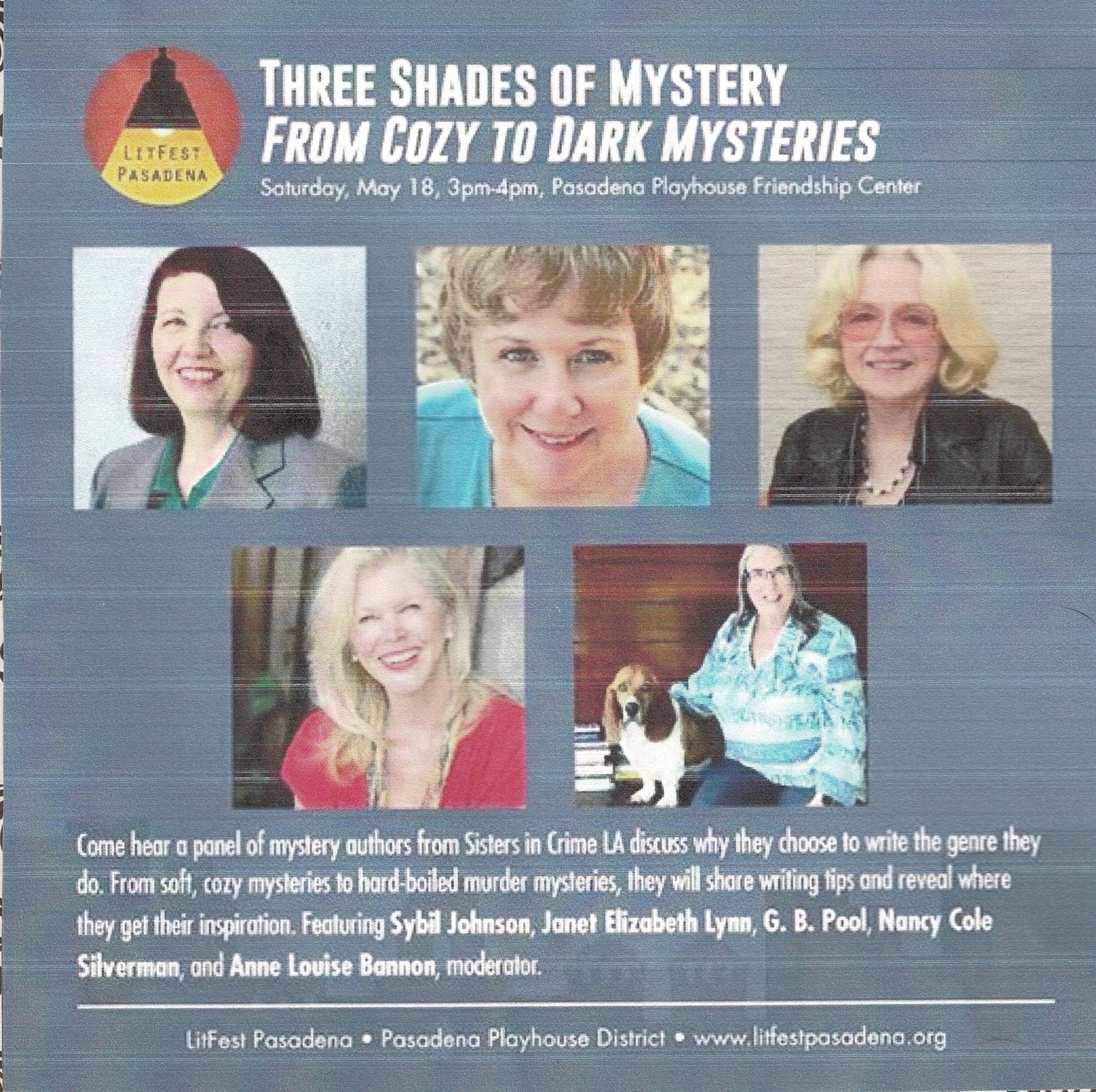

We can use words to assure clarity of thought, or to deliberately deceive. Red herrings in mysteries fall into the latter category, as do ambiguous phrases meant to mislead the reader into thinking something the author intends to prove wrong later. I’ve done this so often in my writing it might be a hallmark of my style.

Words have the power to calm and reassure, to encourage and inspire, or to agitate and inflame. Think of all the influential speeches you’ve heard or read, or the memorable phrases culled from them. Whether by actors reading from a script, politicians addressing their constituents, or activists crusading for their cause, their words, carefully chosen with deliberation, hold the power to move people. To bolster their spirits, or shock them. Convince them they’re right, or maybe, just maybe, they’re not.

All have one thing in common: Someone, or some ones, wrote those words.

Not to equate a frothy page-turner with The Gettysburg Address, but I celebrate writers who celebrate the written word. I commiserate with writers who agonize over the best way to express their or their characters’, thoughts. I respect writers for what they try to accomplish whenever they put pen to paper or fingers on the keyboard.

That’s why we deserve a formal representation for what we do.

The practice of medicine has a symbol – a caduceus with two snakes coiled around it. The symbol of law is the scales of justice. No formal symbol of writing exists, although if you Google it you’ll find cartoons of a hand holding a pencil or pen.

What do you think would make an apt symbol for writers?

Miko Johnston, a founding member of The Writers in Residence, is the author of the historical fiction series, “A Petal in the Wind”, as well as a contributor to several anthologies including the recently released “Whidbey Island: An Insider’s Guide”. Miko lives in Washington (the big one) with her rocket scientist husband. Contact her at mikojohnstonauthor@gmail.com

Some writers snatch a few moments of time wherever they find it. Others adhere to strict schedules. Walter Mosley tells us to write every day. Peter Brett wrote his first novel on his smartphone during his daily travels on the F train. Do you follow a set writing schedule? Write every day? Have a favorite writing spot? Do you put ‘butt to chair’ until you’ve finished a specific word count? Tell us about your writing schedule.

Some writers snatch a few moments of time wherever they find it. Others adhere to strict schedules. Walter Mosley tells us to write every day. Peter Brett wrote his first novel on his smartphone during his daily travels on the F train. Do you follow a set writing schedule? Write every day? Have a favorite writing spot? Do you put ‘butt to chair’ until you’ve finished a specific word count? Tell us about your writing schedule.

My novelist career took off when I went from being a features writer on a well-known women’s magazine to prison.

My novelist career took off when I went from being a features writer on a well-known women’s magazine to prison.

You must be logged in to post a comment.