by Miko Johnston

Unlike some of you, I never took creative writing classes. Early in my adult life, thanks to dropping out of college, I floundered in various low-level clerical positions to earn my way, but writing was my dream job. By luck I got to meet a writer whom I admired, and told him of my goal. “I want to be a writer,” I said. He responded, “Then why aren’t you?” I realized I’d asked a meaningless question. I should have been more specific – “I want to write professionally”. That’s when I returned to college and eventually became a journalist. I lost that career after a car crash and five year recovery period. Still, the urge to write persisted.

About forty years ago I decided to switch to writing fiction and began working on a series of short stories based on a childhood pet, thinking they might make good children’s books. I showed them to a good friend, who knew me ‘back when’, as well as the critter in question. I thought the stories were cute, funny and clever; as the character grew up, the storylines and maturity of the writing grew with her. My friend’s reaction? “They’re terrible.” Disheartened, I filed the stories away in a drawer. Care to guess how long it took for me to write again?

Eventually I dipped my toe in the writing world once more, this time with the idea of writing a novel. I slowly built my skills by writing, studying authors whom I respected, and reading books on the subject, but mostly by participating in writers groups.

I joined an established critique group about twenty-five years ago, where I met several of my fellow WInRs. I credit the core members with guiding me though the completion and polishing of my manuscript for publication, and like most who stuck around in the group, I eventually did get it published.

I can still recall presenting Chapters 1 – 5 of what is now my first novel, A Petal in the Wind. I’d compressed what eventually became my entire novel into fifty pages. I also recall the group’s unanimous opinion: to put it kindly, not good, but they explained WHY. No character development, hardly any scene setting or sensory details, and worst of all, an unrealistic reaction by my protagonist, thereby committing the worst crime in fiction by presenting a totally unbelievable situation. Their comments were tough to hear, but I listened and took them to heart. The next time I presented pages for critique, I received a very different response.

I can still recall presenting Chapters 1 – 5 of what is now my first novel, A Petal in the Wind. I’d compressed what eventually became my entire novel into fifty pages. I also recall the group’s unanimous opinion: to put it kindly, not good, but they explained WHY. No character development, hardly any scene setting or sensory details, and worst of all, an unrealistic reaction by my protagonist, thereby committing the worst crime in fiction by presenting a totally unbelievable situation. Their comments were tough to hear, but I listened and took them to heart. The next time I presented pages for critique, I received a very different response.

I see now the group doubted my ability to write well, based on my initial submission, a reasonable assumption. However, the next time I presented pages, which incorporated their suggestions and advice, the revisions not only impressed them, but convinced them I could do this. Frankly, it convinced me as well. The group treated me differently from then on.

Whenever my turn for submitting pages came up, they mixed praise for the good stuff with very useful suggestions for the problematic parts. Some members had a specialty; one focused on the big picture issues, while another (okay, it was Jackie Houchin) scrutinized each word with forensic precision. The group kept me going with positive and constructive feedback until I finished my first draft. When I presented multiple premises for my follow-up book, their comments helped me find the right path forward in continuing my saga.

I also learned how to give critique. In one of my first meetings, I listened to a short story being read aloud by the writer (okay, it was Jackie Houchin), and all I could contribute was a fashionable woman wouldn’t be wearing a white in winter. With the practice that came with reading or hearing pages from other writers, and picking up clues from their critiques, I began to develop sharper skills for evaluating the good and the not-so-good, not only other’s work, but in my own.

This year I celebrate the twentieth anniversary of my first publishing contract. It would never have happened if not for the support and encouragement of my writers group. Nor would it have happened if I’d disregarded their feedback, or became so insulted by it I’d left the group.

I can take some credit for this, but much should go to the core members. They always knew the boundary line between critique and criticism. Others crossed that line, but thankfully they did not remain in the group for very long because they usually could not accept anything beyond praise for their work. Their loss.

I’ve had the opportunity to pay it forward over the years, in critique groups and through my volunteer work with a local high school creative writing class. Occasionally someone who finds out I’m a published author will ask me to evaluate their writing. The lessons I’ve learned through my groups have helped me do that in a positive, yet helpful way.

Learning the difference between criticism and critique is crucial to the process. Critique must be reassuring, especially when you’re calling out the problems in someone’s writing. Criticism is merely negative. Criticism says something isn’t good, while critique may say that but also explain why. Good critique supports the writer, and encourages them by separating the good from the what-could-be-good-if…. It’s uplifting. It pushed you forward, whereas criticism beats you down.

What if I’m asked to critique a piece that may be beyond redemption? That’s when it helps to have a few key phrases, and a list of recommended reading. I find something, anything to praise or comment favorably on, even if it’s a character’s name. I’ll pick one salvageable problem with the writing and suggest a generic solution. Perhaps there’s too much repetition, the dialog’s clunky, or the genre is unclear. I admit some writers shouldn’t be given false hope, but I needn’t be completely discouraging. I might also remind them there’s nothing wrong with writing for one’s own pleasure, or journaling about one’s life (and keeping it private).

I recently found my pet stories and reread them. Granted, many needed work, but unlike the response I got from my friend, they weren’t awful. Sad that it discouraged me for years, delaying me from doing what I always wanted to do. But I’m writing now, and will continue to do so, having learned the difference between criticism and critique.

On another note, I always love to receive and read your comments, but forgive me if I don’t respond immediately. Today’s post coincides with my 25th wedding anniversary, so hubby and I will be off celebrating. I promise to get back to you soon.

#

Miko Johnston, a founding member of The Writers in Residence, is the author of the historical fiction series, “A Petal in the Wind”, as well as a contributor to several anthologies including the about-t0-be-released “Whidbey Island: An Insider’s Guide”. Miko lives in Washington (the big one) with her rocket scientist husband. Contact her at mikojohnstonauthor@gmail.com

.

This story by Miko Johnston was posted by Jackie Houchin

Three days later Allan and I bid ahoj to Prague and boarded a train bound for Poland. After an overnight stop in Katowice, the largest city in the region known as Upper Silesia, we took a cab to the nearby city of Bytom, the hometown of my father and his entire family. Back then Upper Silesia was part of Germany, the city known as Beuthen. As I walked along the streets, I tried to picture what his life must have been like. I gazed at the people who passed, wondering if I’d see any signs of familiarity in their faces.

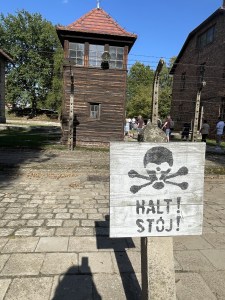

Three days later Allan and I bid ahoj to Prague and boarded a train bound for Poland. After an overnight stop in Katowice, the largest city in the region known as Upper Silesia, we took a cab to the nearby city of Bytom, the hometown of my father and his entire family. Back then Upper Silesia was part of Germany, the city known as Beuthen. As I walked along the streets, I tried to picture what his life must have been like. I gazed at the people who passed, wondering if I’d see any signs of familiarity in their faces. Entering into the first camp, with its ARBEIT MACHT FREI (“Work sets you free”) sign over the entrance gate, I wondered how I would react, or feel. I’m still not sure, to be honest, other than the eerie familiarity of what I heard and saw – from decades of studying photographs accompanied by written accounts, of documentaries and movies filmed on location, and stories I’d heard from survivors, including my father. For many, the trip was a history lesson. For me, it was akin to visiting the cemetery; I lost an estimated ninety members of my family there.

Entering into the first camp, with its ARBEIT MACHT FREI (“Work sets you free”) sign over the entrance gate, I wondered how I would react, or feel. I’m still not sure, to be honest, other than the eerie familiarity of what I heard and saw – from decades of studying photographs accompanied by written accounts, of documentaries and movies filmed on location, and stories I’d heard from survivors, including my father. For many, the trip was a history lesson. For me, it was akin to visiting the cemetery; I lost an estimated ninety members of my family there. After a brief break, the tour continued to nearby Birkenau. Unlike Auschwitz, which to me felt small and claustrophobic, Birkenau is huge. You’ve seen it in many movies: a long low building with railroad tracks leading to a central tower, open at the bottom to allow trains to enter with their human cargo, like a gaping maw ready to devour all who arrive. Alongside and beyond the entrance, what seems like miles and miles of barbed wire fencing surrounds a huge open area interspersed with low barracks and guard towers. In the distance I could see different tour groups traversing the grounds, and for one brief moment I pictured them in the striped uniforms and hats of prisoners.

After a brief break, the tour continued to nearby Birkenau. Unlike Auschwitz, which to me felt small and claustrophobic, Birkenau is huge. You’ve seen it in many movies: a long low building with railroad tracks leading to a central tower, open at the bottom to allow trains to enter with their human cargo, like a gaping maw ready to devour all who arrive. Alongside and beyond the entrance, what seems like miles and miles of barbed wire fencing surrounds a huge open area interspersed with low barracks and guard towers. In the distance I could see different tour groups traversing the grounds, and for one brief moment I pictured them in the striped uniforms and hats of prisoners.  Prior to abandoning the camp in January 1945, days ahead of the advancing Russian forces, the Nazis burned the meticulous records they’d kept of all who were brought to the camps and blew up the gas chambers. Only piles of rubble remain. Many, many piles. They left behind the prisoners too weak to continue; the rest (including my father) went on a forced march from one concentration camp to the next, always trying to stay ahead of the Russians, whom they rightfully feared more than the other Allies. It took several more months until my father was liberated, but at least the Americans freed him. Had he stayed behind in Auschwitz, he would have lived the rest of his life under the thumb of the Soviets. After what I saw in Bytom, I’m grateful he had the strength to wait.

Prior to abandoning the camp in January 1945, days ahead of the advancing Russian forces, the Nazis burned the meticulous records they’d kept of all who were brought to the camps and blew up the gas chambers. Only piles of rubble remain. Many, many piles. They left behind the prisoners too weak to continue; the rest (including my father) went on a forced march from one concentration camp to the next, always trying to stay ahead of the Russians, whom they rightfully feared more than the other Allies. It took several more months until my father was liberated, but at least the Americans freed him. Had he stayed behind in Auschwitz, he would have lived the rest of his life under the thumb of the Soviets. After what I saw in Bytom, I’m grateful he had the strength to wait.

Petal in the Wind Book IV: Lala Smetana

Petal in the Wind Book IV: Lala Smetana

You must be logged in to post a comment.