“The pen is like the needle of a record player held in one’s hand,” Donald Jackson, calligrapher, and scribe to the Late Elizabeth II, once observed. “As it moves across the paper, it releases the music of our innermost selves.”

Wow. I just love that. Sadly if Mr Jackson saw my handwriting he would accurately surmise that I am permanently scattered.

Mahatma Gandhi declared that a poor hand is “the sign of an imperfect education.” But mine leans more towards P.G. Wodehouse who said his, “resembled the movements of a fly that had fallen into an inkpot, and subsequently taken a little brisk exercise.”

Computer keyboards ruined everything for me.

I had the most perfect handwriting. As a Brit we were not trained to write “cursive” which I think is an American form of script. Here is an excerpt from my Home Economics book circa 1969 – please note the hilarious and dated content.

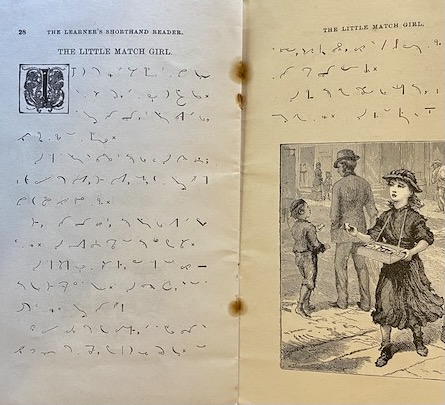

In 1977 I trained as a “shorthand typist” before Dictaphones were invented. In the UK the shorthand was Pitman shorthand; – in the USA it was “Gregg,” although there are many other forms like Teeline or Fastnotes. I could boast 125 wpm (words-per-minute). I loved it. Here is an example of Pitman shorthand taken from “The Lerner’s Shorthand Reader” circa 1892 and priced at 6d.

Isn’t it pretty? If you’d like me to transcribe, I will …

I could “touch type” i.e. there were no letters on the keyboard so I would type the copy without looking at my hands (for those youngsters out there who have never heard the expression). There was also something immensely satisfying about coming to the end of the line and pushing the lever of the carriage return to be rewarded with a cheerful ting!

With the advent of computers, my typing has speeded up dramatically (I just did a free test) and it’s 75 wpm. There is no way my handwriting now could keep up with my brain. Unfortunately, I can hardly hold a pen let alone write with one.

But let’s not forget the reality of handwriting of centuries past. It’s tempting to think that 19th century penmanship was beautiful and legible. This was not the case. Paper, ink, and postage was expensive. People wrote as small as they could. Anne Brontë’s famous final letter had the lines criss-crossing each other. So even if 21st century handwriting has deteriorated, in the big scheme of things, that’s nothing new. Sadly, a recent survey found that in the past five years, 12% of Britons have written nothing at all – not even a note. With the demise of the check book here in the UK, signatures are barely needed either. Some people don’t even have a PEN!!! I was at the post office recently using my USA credit card which demanded a signature to find that I was the only person in the store who carried a pen!

“When you type on a screen, the words seem as fleeting as rays of light. When you write, there’s a real physicality to it that adds another dimension to how you experience your own writing. It fosters a deeper engagement with the material you write, makes the writing voice inside your head clearer and louder.” Quote from Omwow blog, https://omwow.com/longhand-writing/

I love that expression “words seem as fleeting as rays of light.”

Handwriting is deliberate and intentional and requires focused attention. It encourages us to be fully present in the moment. Neat and well-formed handwriting can also indicate a level of discipline and organization. It’s also lovely to receive a handwritten note. It feels personal because it is personal. Someone has taken the time to write and not just zip off an email.

In the meantime, I’m just grateful that my appalling handwriting doesn’t get me into the following kind of trouble:

In 1636 an employee of the East India Company in London wrote to a colleague in India asking that he ‘send me by the next ship 2 or 3 apes.’ Unfortunately – his letter ‘r’ in the word OR caused some confusion. As a result, he received 80 monkeys, together with a note saying that the remaining 123 would be with him shortly.

What about your handwriting? Please share and shame mine.

Three days later Allan and I bid ahoj to Prague and boarded a train bound for Poland. After an overnight stop in Katowice, the largest city in the region known as Upper Silesia, we took a cab to the nearby city of Bytom, the hometown of my father and his entire family. Back then Upper Silesia was part of Germany, the city known as Beuthen. As I walked along the streets, I tried to picture what his life must have been like. I gazed at the people who passed, wondering if I’d see any signs of familiarity in their faces.

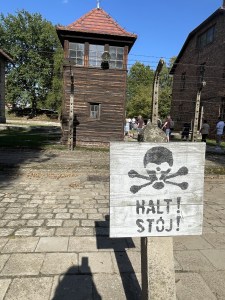

Three days later Allan and I bid ahoj to Prague and boarded a train bound for Poland. After an overnight stop in Katowice, the largest city in the region known as Upper Silesia, we took a cab to the nearby city of Bytom, the hometown of my father and his entire family. Back then Upper Silesia was part of Germany, the city known as Beuthen. As I walked along the streets, I tried to picture what his life must have been like. I gazed at the people who passed, wondering if I’d see any signs of familiarity in their faces. Entering into the first camp, with its ARBEIT MACHT FREI (“Work sets you free”) sign over the entrance gate, I wondered how I would react, or feel. I’m still not sure, to be honest, other than the eerie familiarity of what I heard and saw – from decades of studying photographs accompanied by written accounts, of documentaries and movies filmed on location, and stories I’d heard from survivors, including my father. For many, the trip was a history lesson. For me, it was akin to visiting the cemetery; I lost an estimated ninety members of my family there.

Entering into the first camp, with its ARBEIT MACHT FREI (“Work sets you free”) sign over the entrance gate, I wondered how I would react, or feel. I’m still not sure, to be honest, other than the eerie familiarity of what I heard and saw – from decades of studying photographs accompanied by written accounts, of documentaries and movies filmed on location, and stories I’d heard from survivors, including my father. For many, the trip was a history lesson. For me, it was akin to visiting the cemetery; I lost an estimated ninety members of my family there. After a brief break, the tour continued to nearby Birkenau. Unlike Auschwitz, which to me felt small and claustrophobic, Birkenau is huge. You’ve seen it in many movies: a long low building with railroad tracks leading to a central tower, open at the bottom to allow trains to enter with their human cargo, like a gaping maw ready to devour all who arrive. Alongside and beyond the entrance, what seems like miles and miles of barbed wire fencing surrounds a huge open area interspersed with low barracks and guard towers. In the distance I could see different tour groups traversing the grounds, and for one brief moment I pictured them in the striped uniforms and hats of prisoners.

After a brief break, the tour continued to nearby Birkenau. Unlike Auschwitz, which to me felt small and claustrophobic, Birkenau is huge. You’ve seen it in many movies: a long low building with railroad tracks leading to a central tower, open at the bottom to allow trains to enter with their human cargo, like a gaping maw ready to devour all who arrive. Alongside and beyond the entrance, what seems like miles and miles of barbed wire fencing surrounds a huge open area interspersed with low barracks and guard towers. In the distance I could see different tour groups traversing the grounds, and for one brief moment I pictured them in the striped uniforms and hats of prisoners.  Prior to abandoning the camp in January 1945, days ahead of the advancing Russian forces, the Nazis burned the meticulous records they’d kept of all who were brought to the camps and blew up the gas chambers. Only piles of rubble remain. Many, many piles. They left behind the prisoners too weak to continue; the rest (including my father) went on a forced march from one concentration camp to the next, always trying to stay ahead of the Russians, whom they rightfully feared more than the other Allies. It took several more months until my father was liberated, but at least the Americans freed him. Had he stayed behind in Auschwitz, he would have lived the rest of his life under the thumb of the Soviets. After what I saw in Bytom, I’m grateful he had the strength to wait.

Prior to abandoning the camp in January 1945, days ahead of the advancing Russian forces, the Nazis burned the meticulous records they’d kept of all who were brought to the camps and blew up the gas chambers. Only piles of rubble remain. Many, many piles. They left behind the prisoners too weak to continue; the rest (including my father) went on a forced march from one concentration camp to the next, always trying to stay ahead of the Russians, whom they rightfully feared more than the other Allies. It took several more months until my father was liberated, but at least the Americans freed him. Had he stayed behind in Auschwitz, he would have lived the rest of his life under the thumb of the Soviets. After what I saw in Bytom, I’m grateful he had the strength to wait. My intent in this post is to once again highlight a side trip on the trickily winding writing-road. Nonetheless, I can’t imagine life these days without writing. And consequently all this thinking stuff—starting with a negative revelation has led me to a new enthusiasm for writing. Writer, or “want to be writer”—the winding road I’m always jabbering about is tricky, but well worth it. And for me, writing what I like to read is definitely going to be an uphill challenge! Though so glad to have actually started my latest.

My intent in this post is to once again highlight a side trip on the trickily winding writing-road. Nonetheless, I can’t imagine life these days without writing. And consequently all this thinking stuff—starting with a negative revelation has led me to a new enthusiasm for writing. Writer, or “want to be writer”—the winding road I’m always jabbering about is tricky, but well worth it. And for me, writing what I like to read is definitely going to be an uphill challenge! Though so glad to have actually started my latest.

Leave a comment