by Miko Johnston

We can plot our stories well, describe settings vividly, and touch on all the senses, but the heart of any story is its characters, and they need more than a heart to make them come alive.

I began writing fiction, or more accurately, learning how to write fiction, while working in a library. It gave me access to numerous books and magazines for self-study. One book in the collection devoted a chapter to creating characters, complete with a checklist of traits and their opposites – outgoing vs shy; scholarly vs uneducated – from which the prospective writer could choose and assemble. I found the idea silly and worse, useless. Whether in my writing or my reading, I want characters to resemble real human beings, only more interesting than the average person. You can’t achieve that by compiling random parts. Just ask Dr. Frankenstein.

We’re told to have our characters want something and then keep it from them, make them fight for it. Good advice, crucial for plot. We must describe them with enough detail so the reader can visualize them; again, good advice. Backstories and bios, family and friends, strengths and flaws, jobs and hobbies or interests. How they dress. What and who they like or dislike. The dark secret in their past that drives them forward or holds them back. These big picture details lay a foundation for characters. However, it takes more to breathe life into them. Whether you call them quirks, idiosyncrasies or eccentricities, these subtle differences add a realistic quality to them.

Although our individual quirks may differ, we all have them, which makes this a commonality. In other words, a human trait.

Think of Robert Crais’ Elvis Cole and his affection for cartoon characters, the dry humor of Nelson DeMille’s John Corey, or the fussy Inspector Poirot and his eggs in Agatha Christie’s mystery series. Master art restorer Gabriel Allon inherited his talent, as well as trauma, from his Holocaust survivor mother. And while we naturally empathize with a blind girl like Marie-Laure in “All The Light We Cannot See”, the way she copes with it makes her mesmerizing.

There are two general types of quirks – nature and nurture. Nature includes those the character was born with, such as personality types or bio-physical traits like an intellectual disability or a club foot. A life experience, whether an acquired taste or an emotionally painful experience, would fall under the nurture category. In all cases, how the character has internalized the trait leads to the quirk.

Quirks have to be worked organically into the story. They shouldn’t be unrooted in the character’s history or biology. They should play a role in the character’s thoughts, emotions or actions. They need to be noticeable, but not too blatant; subtle, but not too vague. Readers need to discover them on their own by being shown the behaviors rather than being told about them.

A character’s quirks can be related to their physicality, the way they dress or groom themselves, their behavior or personality, or they can be completely random. Here’s one example: money. Most everyone I’ve met has a philosophy, or criteria, about what they’re willing to spend on something. They’ll be tight-fisted about some things and looser, even extravagant about others. What does it say about a character who’ll spend hundreds of dollars on tickets to the opera, a Broadway play, or the Superbowl, but won’t pay two dollars for a can of tuna in the supermarket unless they get a double-off coupon? Or worse, not buy it at all because they can remember when it cost thirty-nine cents? It says they’re “human”.

Ultimately, it’s not so much a matter of “what” a character does or doesn’t do, what they like or dislike, that makes them full-fledged humans. It’s the “why” that makes it interesting and brings them to life. Always listen to your character, for they’ll often tell you what’s right for them. For hints on this, see Gayle’s earlier post.

When treading the fine line between character and caricature, here’s what to avoid:

- Cliched or overused idiosyncrasies. If I had a dollar for every alcoholic PI, or divorced or widowed detective, I could pay my cable bill for a year. If you’ve seen it before, add a new twist. If you’ve seen it over and over again, avoid it like the plague (humor intended).

- An assemblage of unrelated quirks, as if selected from a list found in a book (jab intended). Author Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe tends his orchids, reads voraciously, and feasts on gourmet food from the comfort of his luxurious home. The genius of his character is how all his passions connect.

- Limit the number of quirks, or else – well, just ask Dr. Frankenstein.

- Don’t overdo the ones you use. Quirks are like seasoning – you need enough to enhance the flavor without overpowering it.

If you found this post helpful, leave a comment, and feel free to contribute your suggestions for making characters come to life. Frankly, my ulterior motive in writing this comes as much from my goal to write books with believable and engrossing characters as my desire to read them.

Miko Johnston, a founding member of The Writers in Residence, is the author of the historical fiction series, “A Petal in the Wind”, as well as a contributor to several anthologies including the about-t0-be-released “Whidbey Island: An Insider’s Guide”. Miko lives in Washington (the big one) with her rocket scientist husband. Contact her at mikojohnstonauthor@gmail.com

I’ve always enjoyed spring, a time of renewal, and probably more so this year after the winter we’ve been through. Thoughts turn from shoveling snow to shoveling dirt in the garden, from watching the overflowing rivers subside to marveling at the regeneration of fauna and flora.

I’ve always enjoyed spring, a time of renewal, and probably more so this year after the winter we’ve been through. Thoughts turn from shoveling snow to shoveling dirt in the garden, from watching the overflowing rivers subside to marveling at the regeneration of fauna and flora. I can still recall presenting Chapters 1 – 5 of what is now my first novel, A Petal in the Wind. I’d compressed what eventually became my entire novel into fifty pages. I also recall the group’s unanimous opinion: to put it kindly, not good, but they explained WHY. No character development, hardly any scene setting or sensory details, and worst of all, an unrealistic reaction by my protagonist, thereby committing the worst crime in fiction by presenting a totally unbelievable situation. Their comments were tough to hear, but I listened and took them to heart. The next time I presented pages for critique, I received a very different response.

I can still recall presenting Chapters 1 – 5 of what is now my first novel, A Petal in the Wind. I’d compressed what eventually became my entire novel into fifty pages. I also recall the group’s unanimous opinion: to put it kindly, not good, but they explained WHY. No character development, hardly any scene setting or sensory details, and worst of all, an unrealistic reaction by my protagonist, thereby committing the worst crime in fiction by presenting a totally unbelievable situation. Their comments were tough to hear, but I listened and took them to heart. The next time I presented pages for critique, I received a very different response. I don’t see joy, or serenity, or even concern in his face. Only resignation. I’d recognized the Charles Bridge in the background so I knew this had been taken in Prague, but based on the other photographs, I had no doubt the location fell behind the Iron Curtain.

I don’t see joy, or serenity, or even concern in his face. Only resignation. I’d recognized the Charles Bridge in the background so I knew this had been taken in Prague, but based on the other photographs, I had no doubt the location fell behind the Iron Curtain.

Three days later Allan and I bid ahoj to Prague and boarded a train bound for Poland. After an overnight stop in Katowice, the largest city in the region known as Upper Silesia, we took a cab to the nearby city of Bytom, the hometown of my father and his entire family. Back then Upper Silesia was part of Germany, the city known as Beuthen. As I walked along the streets, I tried to picture what his life must have been like. I gazed at the people who passed, wondering if I’d see any signs of familiarity in their faces.

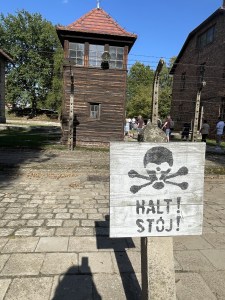

Three days later Allan and I bid ahoj to Prague and boarded a train bound for Poland. After an overnight stop in Katowice, the largest city in the region known as Upper Silesia, we took a cab to the nearby city of Bytom, the hometown of my father and his entire family. Back then Upper Silesia was part of Germany, the city known as Beuthen. As I walked along the streets, I tried to picture what his life must have been like. I gazed at the people who passed, wondering if I’d see any signs of familiarity in their faces. Entering into the first camp, with its ARBEIT MACHT FREI (“Work sets you free”) sign over the entrance gate, I wondered how I would react, or feel. I’m still not sure, to be honest, other than the eerie familiarity of what I heard and saw – from decades of studying photographs accompanied by written accounts, of documentaries and movies filmed on location, and stories I’d heard from survivors, including my father. For many, the trip was a history lesson. For me, it was akin to visiting the cemetery; I lost an estimated ninety members of my family there.

Entering into the first camp, with its ARBEIT MACHT FREI (“Work sets you free”) sign over the entrance gate, I wondered how I would react, or feel. I’m still not sure, to be honest, other than the eerie familiarity of what I heard and saw – from decades of studying photographs accompanied by written accounts, of documentaries and movies filmed on location, and stories I’d heard from survivors, including my father. For many, the trip was a history lesson. For me, it was akin to visiting the cemetery; I lost an estimated ninety members of my family there. After a brief break, the tour continued to nearby Birkenau. Unlike Auschwitz, which to me felt small and claustrophobic, Birkenau is huge. You’ve seen it in many movies: a long low building with railroad tracks leading to a central tower, open at the bottom to allow trains to enter with their human cargo, like a gaping maw ready to devour all who arrive. Alongside and beyond the entrance, what seems like miles and miles of barbed wire fencing surrounds a huge open area interspersed with low barracks and guard towers. In the distance I could see different tour groups traversing the grounds, and for one brief moment I pictured them in the striped uniforms and hats of prisoners.

After a brief break, the tour continued to nearby Birkenau. Unlike Auschwitz, which to me felt small and claustrophobic, Birkenau is huge. You’ve seen it in many movies: a long low building with railroad tracks leading to a central tower, open at the bottom to allow trains to enter with their human cargo, like a gaping maw ready to devour all who arrive. Alongside and beyond the entrance, what seems like miles and miles of barbed wire fencing surrounds a huge open area interspersed with low barracks and guard towers. In the distance I could see different tour groups traversing the grounds, and for one brief moment I pictured them in the striped uniforms and hats of prisoners.  Prior to abandoning the camp in January 1945, days ahead of the advancing Russian forces, the Nazis burned the meticulous records they’d kept of all who were brought to the camps and blew up the gas chambers. Only piles of rubble remain. Many, many piles. They left behind the prisoners too weak to continue; the rest (including my father) went on a forced march from one concentration camp to the next, always trying to stay ahead of the Russians, whom they rightfully feared more than the other Allies. It took several more months until my father was liberated, but at least the Americans freed him. Had he stayed behind in Auschwitz, he would have lived the rest of his life under the thumb of the Soviets. After what I saw in Bytom, I’m grateful he had the strength to wait.

Prior to abandoning the camp in January 1945, days ahead of the advancing Russian forces, the Nazis burned the meticulous records they’d kept of all who were brought to the camps and blew up the gas chambers. Only piles of rubble remain. Many, many piles. They left behind the prisoners too weak to continue; the rest (including my father) went on a forced march from one concentration camp to the next, always trying to stay ahead of the Russians, whom they rightfully feared more than the other Allies. It took several more months until my father was liberated, but at least the Americans freed him. Had he stayed behind in Auschwitz, he would have lived the rest of his life under the thumb of the Soviets. After what I saw in Bytom, I’m grateful he had the strength to wait.

The joy of receiving cards offsets much of that nostalgia. I often get to see pictures of the family and hear about their adventures over the past year. Some of the news may not be happy, but the contact always is. I set up all my cards along the living room and dining room windows, each one like a handshake, or hug, from someone dear. When I remove them in early January I take a moment to reflect on the cards that are missing, a reminder of those I’ve lost, either in body, or in mind, or who’ve just drifted away.

The joy of receiving cards offsets much of that nostalgia. I often get to see pictures of the family and hear about their adventures over the past year. Some of the news may not be happy, but the contact always is. I set up all my cards along the living room and dining room windows, each one like a handshake, or hug, from someone dear. When I remove them in early January I take a moment to reflect on the cards that are missing, a reminder of those I’ve lost, either in body, or in mind, or who’ve just drifted away. For me the best part of holiday gifts isn’t receiving them, but writing thank you cards. Like the holiday cards, it starts with finding the right card for the person to be thanked. I have an assortment of stationery with different designs, ranging from charming illustrations to an embossed THANK YOU. I favor classic white or cream notes with matching or coordinating envelopes. Then there’s the challenge of coming up with something fresh, sincere and meaningful to write, just the type of challenge I relish.

For me the best part of holiday gifts isn’t receiving them, but writing thank you cards. Like the holiday cards, it starts with finding the right card for the person to be thanked. I have an assortment of stationery with different designs, ranging from charming illustrations to an embossed THANK YOU. I favor classic white or cream notes with matching or coordinating envelopes. Then there’s the challenge of coming up with something fresh, sincere and meaningful to write, just the type of challenge I relish.

You must be logged in to post a comment.