by Guest Blogger, Tammy D. Walker

Writing dialogue can be difficult. First, there’s the content of what the characters say. And then, there’s the subtext, or what the characters are trying to communicate to each other without saying something that might be too awkward or imperiling for them to say directly. And, also, there are the actual words that need to go between those harrowing quote marks.

As readers, we want what characters say to sound realistic, even though, as writers, we understand that the best-sounding dialogue in the context of a story might strike us as odd if we heard it in real life.

So how do we balance all these moving parts to make them work as solid dialogue?

One solution I’d like to offer is to use techniques from crafting poetry.

Before I started writing mysteries, I’d had a couple collections of poetry published, and I studied the form in grad school. And while I find writing poems and novels to be quite different in most ways, I did find that the “ear training” required for writing poems has helped me fine tune my dialogue writing process.

Though most of the poems we encounter are in print, poetry is still a very auditory art, meant, for the most part, to be read aloud. So when I’m thinking about how to construct dialogue, I apply the same sound-related techniques in writing poems as I do while writing dialogue. Though dialogue in fiction, like poems, isn’t generally read aloud, we should still consider its sound and how that sound serves the story.

Writing poetry requires the poet to not only think about individual words but also their arrangement in syntactic units, in lines, and in juxtaposed groupings. As fiction writers, we can apply these ideas to writing dialogue to give our characters words that make them more compelling to our readers.

Countering Some Possible Objections

Let’s just get something out of the way, first: Poetry has a reputation among the general public for being obscure, enigmatic, and perhaps also stodgy. Which, I think, is unfair. The poems most of us encountered in high school are throw-backs to previous centuries, when flowery language twisted harder than barbed wire to fit the perimeter of some rigid form might well have kept all but the most diligent reader out of the green pastures of meaning.

Okay, maybe I took that metaphor too far. But I think you’ll get my meaning.

Contemporary poetry, and that leading up to it in the last century, relies on plainer language. Sure, there’s metaphor, simile, and all the other techniques we learned about in freshman English class, but there’s also a directness and freshness to language used now. Victorian poems were written for Victorian audiences; poems written in the 2020s were meant to be read by, well, you and me. In general, the language is accessible by your average reader.

So, for the most part, the language in this poetry-techniques-in-dialogue should be what your character would use in day-to-day life.

Unless you don’t want them to, of course.

What the Characters Say

So, that out of the way, let’s get to content.

Before I write either a poem or a scene, I first think about what the content of the poem or the scene and outline what needs to take place. For a scene, of course, that means thinking about what the characters want and how they’ll either achieve that or how I can thwart them. For a poem (and yes, I outline my poems before I begin drafting) I think about the arc of the poem, or what argument the speaker of the poem will make.

(A note on terms: even though many poems are autobiographical–or even confessional–many aren’t, including almost all of mine. The “I” of the poem is the speaker, who may or may not be the poet, so it’s useful in this context to think about the poem as spoken by a character, even if that character functions more as a narrator than a in-the-scene actor.)

Since most of my fiction these days is cozy mystery, I’ll use examples from that genre. Let’s say we have two characters, Curtis, an art collector and one of the suspects in my novel Venus Rising, and Amy, a librarian intent on solving the mystery of a painting at the center of the book’s mystery.

Since most of my fiction these days is cozy mystery, I’ll use examples from that genre. Let’s say we have two characters, Curtis, an art collector and one of the suspects in my novel Venus Rising, and Amy, a librarian intent on solving the mystery of a painting at the center of the book’s mystery.

Amy joins Curtis for dinner in his suite. She wants to know more about his art collection, but, of course, being a good amateur detective, she can’t ask her pointed questions directly. But she’s there to gather information. Curtis, on the other hand, just wants to impress Amy. So this gives me both Amy’s content–she wants information–and Curtis’s–he just wants Amy.

How the Characters Say It

So now we know what the characters want to say. But Amy can’t tip her hand about her suspicions just yet, and Curtis can’t come on too strong. Let’s go back to a few ideas from poetry about wording, rhythm, line length, and syntactic units.

Curtis wants to woo Amy, and his language is more song-like. The rhythm of the words is more lilting. He calls Amy “A vision in aquamarine,” and later asks “Champagne for my lovely companion?”

To which Amy replies, “I don’t drink.” Her words here are clipped and emphatic. (She’s caught on to Curtis’s intentions by this point, and she has no interest in him.)

The rhythm of the words in this short example show how differently the characters are approaching each other. The words themselves are also worth noting, as Curtis uses Latinate language (“vision,” “aquamarine,” and “companion”) to inflate is dialogue, whereas Amy’s more Germanic retort punches back.

Line length is also key to establishing rhythm and the perceived speed at which the dialogue is spoken by characters. While dialogue isn’t split by line or stanza breaks in the way poems are, it can be split by tags (“she said,” for instance) or by the end of a sentence.

Longer lines tend to quicken a reader’s pace. Shorter lines, conversely, slow it. Poems such as H. D.’s “We Two” cause us to stop more often at the ends of short lines: “We two are left: / I with small grace reveal / distaste and bitterness[.]” Poems with longer lines draw us forward at a quicker pace. W. B. Yeats’s “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” does just this: “And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow, / Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings[.]”

So as I’m writing dialogue, I think about whether I want the character to speak quickly, perhaps revealing their anxiety, or slowly, to reveal their uncertainty. And then, from there, I’ll decide whether to use longer or shorter words in longer or shorter phrases, and how I’ll either break them (or not) with tags, interruptions, or actions.

In this example, I wanted to show Amy’s distaste for Curtis, even though she can’t reveal the fact that she does not like him just yet, since she needs to know more about his art collection. She backtracks a bit and later says, “Sparkling water would be lovely, thank you.” I wanted to move her more toward Curtis’s rhythm and longer lines, so that she doesn’t reveal her suspicions too soon.

Concluding Remarks Using the Best Words

One of the concerns of poets in the early 20th century was that the language of poems had been, too often, contorted to fit forms, and that the resulting work sounded contrived and unnatural. This carries forward through contemporary poetry, and poets do strive to make the sounds of the words, lines, and syntactic units fit with, complicate, and enrich the arguments of their poems.

This concern with the naturalness of language is also useful to fiction writers crafting dialogue. We want the content of what our characters say to sound natural. Considering the content in light of poetic sound craft can give the characters compelling things to say in a way that enriches the characters themselves and their movements through the story.

Which is an aim that, I hope you’ll agree, sounds good.

#

Bio: Tammy D. Walker writes mysteries, poetry, and science fiction. Her debut cozy mystery, Venus Rising, was published by The Wild Rose Press in 2023. As T.D. Walker, she’s the author of three poetry collections, most recently Doubt & Circuitry (Southern Arizona Press, 2023). When she’s not writing, she’s probably reading, trying to find far-away stations on her shortwave radios, or enjoying tea and scones with her family. Find out more at her website: https://www.tammydwalker.com

#

Tammy D. Walker’s article is posted by member, Jackie Houchin (Don’t you want to run out and buy her cozy mystery to see how she does this? Wow!)

Three days later Allan and I bid ahoj to Prague and boarded a train bound for Poland. After an overnight stop in Katowice, the largest city in the region known as Upper Silesia, we took a cab to the nearby city of Bytom, the hometown of my father and his entire family. Back then Upper Silesia was part of Germany, the city known as Beuthen. As I walked along the streets, I tried to picture what his life must have been like. I gazed at the people who passed, wondering if I’d see any signs of familiarity in their faces.

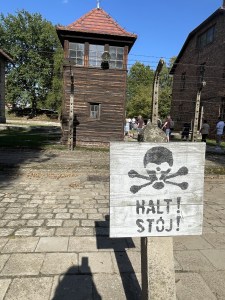

Three days later Allan and I bid ahoj to Prague and boarded a train bound for Poland. After an overnight stop in Katowice, the largest city in the region known as Upper Silesia, we took a cab to the nearby city of Bytom, the hometown of my father and his entire family. Back then Upper Silesia was part of Germany, the city known as Beuthen. As I walked along the streets, I tried to picture what his life must have been like. I gazed at the people who passed, wondering if I’d see any signs of familiarity in their faces. Entering into the first camp, with its ARBEIT MACHT FREI (“Work sets you free”) sign over the entrance gate, I wondered how I would react, or feel. I’m still not sure, to be honest, other than the eerie familiarity of what I heard and saw – from decades of studying photographs accompanied by written accounts, of documentaries and movies filmed on location, and stories I’d heard from survivors, including my father. For many, the trip was a history lesson. For me, it was akin to visiting the cemetery; I lost an estimated ninety members of my family there.

Entering into the first camp, with its ARBEIT MACHT FREI (“Work sets you free”) sign over the entrance gate, I wondered how I would react, or feel. I’m still not sure, to be honest, other than the eerie familiarity of what I heard and saw – from decades of studying photographs accompanied by written accounts, of documentaries and movies filmed on location, and stories I’d heard from survivors, including my father. For many, the trip was a history lesson. For me, it was akin to visiting the cemetery; I lost an estimated ninety members of my family there. After a brief break, the tour continued to nearby Birkenau. Unlike Auschwitz, which to me felt small and claustrophobic, Birkenau is huge. You’ve seen it in many movies: a long low building with railroad tracks leading to a central tower, open at the bottom to allow trains to enter with their human cargo, like a gaping maw ready to devour all who arrive. Alongside and beyond the entrance, what seems like miles and miles of barbed wire fencing surrounds a huge open area interspersed with low barracks and guard towers. In the distance I could see different tour groups traversing the grounds, and for one brief moment I pictured them in the striped uniforms and hats of prisoners.

After a brief break, the tour continued to nearby Birkenau. Unlike Auschwitz, which to me felt small and claustrophobic, Birkenau is huge. You’ve seen it in many movies: a long low building with railroad tracks leading to a central tower, open at the bottom to allow trains to enter with their human cargo, like a gaping maw ready to devour all who arrive. Alongside and beyond the entrance, what seems like miles and miles of barbed wire fencing surrounds a huge open area interspersed with low barracks and guard towers. In the distance I could see different tour groups traversing the grounds, and for one brief moment I pictured them in the striped uniforms and hats of prisoners.  Prior to abandoning the camp in January 1945, days ahead of the advancing Russian forces, the Nazis burned the meticulous records they’d kept of all who were brought to the camps and blew up the gas chambers. Only piles of rubble remain. Many, many piles. They left behind the prisoners too weak to continue; the rest (including my father) went on a forced march from one concentration camp to the next, always trying to stay ahead of the Russians, whom they rightfully feared more than the other Allies. It took several more months until my father was liberated, but at least the Americans freed him. Had he stayed behind in Auschwitz, he would have lived the rest of his life under the thumb of the Soviets. After what I saw in Bytom, I’m grateful he had the strength to wait.

Prior to abandoning the camp in January 1945, days ahead of the advancing Russian forces, the Nazis burned the meticulous records they’d kept of all who were brought to the camps and blew up the gas chambers. Only piles of rubble remain. Many, many piles. They left behind the prisoners too weak to continue; the rest (including my father) went on a forced march from one concentration camp to the next, always trying to stay ahead of the Russians, whom they rightfully feared more than the other Allies. It took several more months until my father was liberated, but at least the Americans freed him. Had he stayed behind in Auschwitz, he would have lived the rest of his life under the thumb of the Soviets. After what I saw in Bytom, I’m grateful he had the strength to wait.

Since most of my fiction these days is cozy mystery, I’ll use examples from that genre. Let’s say we have two characters, Curtis, an art collector and one of the suspects in my novel Venus Rising, and Amy, a librarian intent on solving the mystery of a painting at the center of the book’s mystery.

Since most of my fiction these days is cozy mystery, I’ll use examples from that genre. Let’s say we have two characters, Curtis, an art collector and one of the suspects in my novel Venus Rising, and Amy, a librarian intent on solving the mystery of a painting at the center of the book’s mystery.

You must be logged in to post a comment.