By Maggie King

“How could I have known that murder could sometimes smell like honeysuckle?”

One of many memorable lines from Double Indemnity (1944), a film I never tire of watching—even after the fifth or sixth time! It’s a film I urge all crime writers to study—whether you’re writing cozies or hard-boiled detective stories. The superb dialogue, with its emphasis on double entendres and provocative banter, not only entertains but moves the plot along. The use of light and shadow create a virtual underworld that emphasizes the unsavoriness of the characters and plot. It is film perfection.

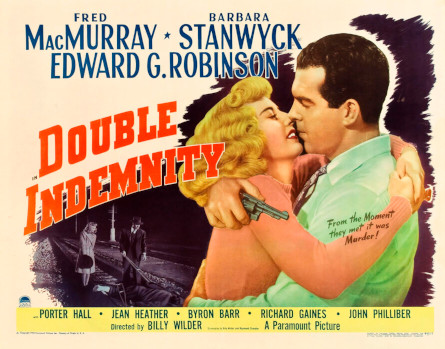

Double Indemnity is the ultimate film noir—it’s dark, steamy, loaded with atmosphere, and the characters are sleazy as all get out. In this story, originally penned by James M. Cain and adapted for the silver screen by Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler, discontented housewife Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) bewitches insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred McMurray) into killing her husband. Together, she promises, they will collect on a double indemnity insurance clause.

Phyllis is film noir’s classic femme fatale, luring a man whose brain goes on hiatus the moment he sees her. Walter seems like a good guy, but he’s no match for the lovely and smoldering Phyllis. She doesn’t even seem good—she’s evil to the core. Since he’s only marginally good, ensnaring him in her web is child’s play. Indeed, Double Indemnity’s best lesson for writers may be its showing how easily someone can be led astray by promises of a lifetime of riches and passion.

Writers are frequently advised to show, not tell. Double Indemnity follows this advice to good effect in its depictions of the life styles of Phyllis and Walter. Phyllis lives in an elegant Spanish house in the hills overlooking the Loz Feliz section of Los Angeles. Walter spends his days selling insurance, operating out of a ubiquitous office building in downtown LA, where the worker bees toil in a pre-cubicle bullpen desk arrangement (I worked in a few bullpen set-ups myself). Evening comes and Walter returns to his cramped apartment not far from his office. The contrast of life styles is stark, but never verbalized, only shown.

When it comes to sex scenes, the censorship of the day forced writers to show without telling, allowing them to achieve higher levels of creativity. Sex was left to the imagination, using suggestive dialogue and longing looks. A scene in Walter’s apartment hints that Walter and Phyllis had just been intimate. You don’t know for sure … but you’re pretty sure.

Elements of Alfred Hitchcock are evident in Double Indemnity. You don’t see the murder but you know it’s happening just out of camera range. Phyllis’s satisfied look and the gleam in her eye are what tell you that her husband is now thoroughly dead.

So … no sex, no violence, no profanity. Sounds like a modern day cozy. Not a chance! Double Indemnity is far from a cozy, and a current version of it would include all three no-nos. Body Heat (1981) is an example.

And there’s the creative way the senses are incorporated into the narration: “How could I have known that murder could sometimes smell like honeysuckle?” and “I couldn’t hear my own footsteps. It was the walk of a dead man.” There are many such quotes in Double Indemnity.

Here’s a quote that sums up the film in a nutshell: “I killed him for money and for a woman. I didn’t get the money. And I didn’t get the woman.”

You can almost feel sorry for Walter—after all, if you go to all the trouble of murdering your lover’s husband, shouldn’t you reap some of the benefits? Perhaps the film’s best lesson for writers is showing how easily someone can be led astray by promises of a lifetime of riches and passion. It makes you wonder how many of us are just a whisper away from evil.

After the murder, things go downhill. For one thing, Walter’s boss, Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson), is highly suspicious of Phyllis’s double indemnity claim and investigates it like a dog with ten bones. And Walter and Phyllis grow to distrust each other (no surprise there). By the time Walter realizes that murdering Mr. Dietrichson wasn’t such a good idea, it’s too late. But is he sorry that he killed the man? Or does he only regret that he’s left with nothing to show for his efforts beyond a bullet in his shoulder?

Often when I re-watch a movie, or re-read a book, I start finding flaws and turn critical. Not so with Double Indemnity. But I will notice something new with each viewing. Like how Barton Keyes never has a match, and Walter Neff has to light his cigar. But in the last scene, it’s Mr. Keyes who lights a cigarette for Mr. Neff (there’s that bullet in his shoulder). An unexpected touching moment.

James M. Cain took his inspiration for Double Indemnity from a real life case. In 1927 a New York woman named Ruth Snyder persuaded her lover, a corset salesman named Judd Gray, to kill her husband. She had recently convinced her spouse to take out a $48,000 insurance policy with a double indemnity clause. For more information on the case, read this Wikipedia article.

I have been watching these old movies all my life. Maybe because they actually tell a story without car chases and blowing everything up. They actually had a plot with a point and character arcs that you could follow showing at least one main character learning something, even if it was finding out they made a huge mistake. I haven’t seen many new movies in the past thirty years, so I have no idea if one or two use Aristotle’s philosophy of having a real plot, good characters, dialogue that advances or enhances the plot, maybe a setting that shows us how the people live, and most of all the meaning behind the story. I’ve come away from the few movies I’ve managed to watch on TV made in the past several decades with one question: What was the point of that story? One or two have one. Most don’t. Writers can do better, if they want to. Just watch an old movie and see how it’s done. Thanks, Maggie. That was an inspirational post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve enjoyed many recent movies, but did they have a point or follow Aristotle’s philosophy? I’d have to think about that. Most movies I would list as all-time favorites came out before 1980. Thanks for your thoughtful comments, Gayle.

LikeLike

For some reason I’ve never seen Double Indemnity (though you’ve put it on my list of must-see movies). Even so, I agree that great films can teach us how to be better writers. During the Hays Code era, filmmakers had to rely on ways to “show” what couldn’t be shown. Those restrictions led to some brilliant scenes and dialogue. They charmed and amused, and sometimes shocked audiences, but with subtlety rather than explicitness. I recall a racy line from the 1975 movie Shampoo that stunned audiences. Within a few years it lost its power to shock, and today you can hear that kind of language everywhere. Yawn.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I saw Shampoo back then but didn’t recall the racy line. According to Google, there were several racy lines. You’re right, they wouldn’t shock these days—we hear worse from politicians. I hope you watch DI and enjoy it. Thanks, Miko.

LikeLike

I’ve certainly heard of Double Indemnity but I don’t think I’ve ever seen it. Sounds like something I should see, though! And learn from. Thanks for telling us about it, Maggie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope you enjoy it, Linda.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I totally agree with you, Maggie. I’ve seen this fine film two or three times, and now I must watch it yet again because I missed some of the points you brought up in your post. BTW, if you ever want a good laugh, catch the Carol Burnett satire of this film. It ranks up there with her take on Gone with the Wind–hilarious!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bonnie, I know you’ll continue to enjoy DI. I used to watch Carol Burnett but don’t recall the satire she did on the film. I’ll have to catch it. Thanks for suggesting.

LikeLike

Those really were the days of good film making! Maggie, this is a wonderful reminder of how rich carefully chosen words can be – and how evocative just simple words like ‘honeysuckle’ can be…

Thank you for taking me back to a magical time of entertainment!

LikeLike